Carmakers Forced by Chip Crisis to Rethink Just-In-Time Ordering

A century after automakers showed the world the value of assembly-line manufacturing, a shortage of semiconductors is teaching the industry a painful new lesson in what it takes to build a car.

For most of its history, the industry has relied on a distinct approach to buying car parts, procuring components from suppliers right at the moment they’re needed. It’s referred to as just-in-time manufacturing and is designed to streamline production and eliminate the costs of keeping warehouses stocked with parts waiting to be used.

But the shortcomings of that system were made starkly clear this year as the automakers confronted a dearth of the chips they need to build advanced functions into their vehicles, and found themselves near the bottom of chipmakers’ customer lists because of their just-in-time approach. That shortage is threatening to cut $110 billion in sales from the industry, and forcing auto manufacturers to overhaul the way they get the electronic components that have become critical to contemporary car design.

Semiconductor makers are demanding guaranteed, long-term orders rather than the short-term flexibility the carmakers are used to. The chipmakers’ assertiveness, even under pressure from lawmakers, underscores the rebalancing of power from the companies whose logos are on the cars to those that provide the advanced technology that runs them.

As these components play a bigger role in everything from in-car entertainment to self-driving functions, chip manufacturers say they’re willing to invest in expanding production to head off a repeat of shortages that have forced the industry to mothball factories and furlough workers -- if the carmakers give them orders that can’t be canceled and commit to long-term agreements.

“Why would I have invested a single dollar when my customer can cancel within 30 days and it takes me two years to build capacity?” ON Semiconductor’s El-Khoury said.

There are signs the industry is listening. Last week, Ford Motor Co. Chief Executive Officer Jim Farley indicated a new willingness to reverse decades of outsourcing for parts.

“As the industry changes, we have to in-source now, just like we in-sourced powertrains in the ’20s and ’30s,” said Farley, who has shut down half his factories and seen his dealers’ lots emptying because of a dearth of chips.

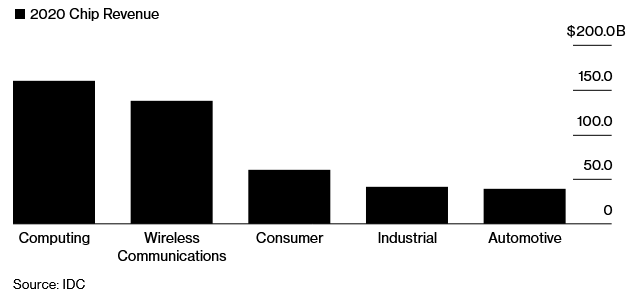

Chipmakers Have More Important Customers

Automotive ranks fifth on list of semiconductor buyers.

“Customers need to change,” said Hassane El-Khoury, chief executive officer of ON Semiconductor Corp., which gets more than a third of its revenue from the automotive market. “That just-in-time mindset doesn’t work.”

Most components used by the auto industry are part of a discrete food chain, and carmakers are at the top, able to orchestrate their suppliers’ actions in a system that delivers them a set of components that can be put together quickly and cheaply into a finished vehicle. Electronics makers, who’ve fared much better in the chip supply crunch, regard semiconductors as essential systems, and they work directly with chipmakers to secure products and often design their devices around the chips themselves.

Automakers can no longer “assume the dominance of an 800-pound gorilla” in negotiations with chip companies and battery makers, said Mark Wakefield, head of the auto practice at consultancy AlixParters.

Pioneered by Toyota Motor Corp. in the 1960s, just-in-time is a system where components suppliers are required to turn up with whatever the carmakers want at the last possible moment in a process that pares costs to the very minimum.

That strategy has served the industry well, saving money and helping it organize a system for sourcing the 40,000 or so components that go into a modern vehicle, many of which can be made in a matter of days. But semiconductors -- the heart of sensors, engine management and battery controllers, infotainment and eventually systems that will pilot vehicles -- are created in a process that takes months. And building and equipping a factory to produce them requires years.

Today’s cars contain an average of 1,400 semiconductors -- and that puts the chipmakers at an advantage. Ford’s Farley said he’s now negotiating contracts directly with chipmakers -- bypassing his traditional auto suppliers -- while building up inventory of the precious pieces and even redesigning models to accommodate the semiconductor companies.

“We have learned a lot through this crisis that can be applied to many critical components,” Farley told analysts last month as he announced Ford would lose half its production in the second quarter and take a $2.5 billion hit to earnings this year, citing a lack of chips. “We’re also thinking about what this means for the world of batteries and silicon and all sorts of other components that are really mission critical for our company.”

Ford is not alone in seeking solutions that upend long-time industry practices. Automakers from General Motors Co. to Volkswagen AG to Tesla Inc. are looking for ways to get closer to the chipmaking process, which could include forming partnerships with semiconductor companies, bringing chipmaking in-house and even building their own foundries. Nothing is off the table.

“Cars are only going to get more technical and they’re going to need more chips,” said Sam Fiorani, vice president of vehicle forecasting at consultant AutoForecast Solutions. “All of the vehicle manufacturers are looking at every possible scenario for getting it solved for the long-term.”

But according to some chipmakers, the auto industry has embraced new technology but failed to understand those that supply it.

“There is a huge difference between manufacturing a car and manufacturing a chip,” said Kurt Sievers, CEO of NXP Semiconductor NV, the biggest maker of auto chips. “We’ve been working for years closely with the auto OEMs directly when it comes to R&D and innovation -- however, not at all for supply chain and volume forecasting.”

Sievers said the chip industry wants specific forecasts that stretch out in years and binding commitments to buy chips that last that long. The way automakers, referred to as original equipment manufacturers or OEMs, and semiconductor vendors work together needs to change, he said.

And the car companies have little choice but to do so. Consumers are increasingly choosing vehicles based on functions such as connectivity, entertainment and advanced automated safety features. The auto industry is steadily shifting away from gasoline to battery power. All of that requires more chips.

“It’s no longer this subsystem that no one cares about,” said Victor Peng, CEO of Xilinx Inc. a chipmaker whose products are uses in advanced driver-assistance systems. “The electronics is really going to shape the customer experience.”

The semiconductor industry has plenty of other orders to fill. In 2020 automakers bought almost $40 billion worth of chips, little changed from the prior year, even amid the crash of the pandemic. By comparison, the computer industry bought 17% more chips than it did in 2019, for a total of $160 billion. Phone makers, meantime, provided the chip industry with $137 billion in revenue, a jump of 12%.

Earlier this year, automakers lobbied U.S. lawmakers to intervene to help them with the shortage, arguing that chipmakers were unfairly prioritizing customers building less important consumer electronics over cars. The automakers argue their industry creates more than 7 million jobs in America and is critical to national security. And they’ve found a sympathetic ear in President Joe Biden, who was supported by the United Auto Workers in the 2020 election, and is working to help the auto industry navigate the chip crisis.

Still, consumer electronics buys $20 billion more chips a year than the auto industry, and Big Tech has plenty of clout in Washington, too.

Chipmakers are also in no hurry to add new factories to meet this year’s chip rush. Though 2020 was a good year and 2021 is shaping up to be even better, they don’t have to look back very far to be reminded of the difficulties of matching supply with short-term fluctuations in demand. In 2019 industry sales shrank 12% as customers slashed orders to work through stockpiles.

Many investors and analysts are already concerned that what now looks like insatiable demand is customers double-ordering: asking for twice the amount they need so they can at least get the number they want. In the past, such heavy ordering has proved to foreshadow industry gluts, with demand eventually easing and buyers tapping the brakes as they worked down accumulated inventory.

“We came out of 2018 guns blazing, everybody hoarded, and then 2019 was an awful year of demand because they already had chips,” said ON Semiconductor’s El Khoury. “Here we are today with people looking at us and asking, ‘why haven’t you invested?’”

The type of chip automakers want also works against them. Much of what they use -- things such as sensors and power regulators -- can be made on what’s called lagging nodes, or production technology that hasn’t been state-of-the-art for years. While that makes it cheaper, chipmakers are reluctant to expand capacity of technology that’s closer to being obsolete.

“The chips that the automotive industry uses are older than the ones you’d find in your cell phones or in your video games,” said AutoForecast Solutions’ Fiorani. “That makes them less of a priority to the companies that produce them.”

originally published bloomberg.com